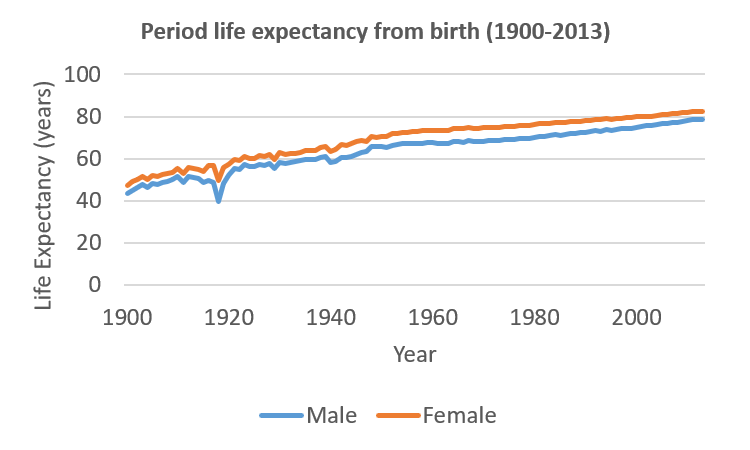

Since the start of the twentieth century, we’ve seen huge improvements in life expectancy. As the chart below for England and Wales shows, a boy born in 1900 might have expected to live for 43.3 years, whilst a girl could expect to have 47.3 years. By 2013, the equivalent numbers were be 78.6 years and 82.4 years.

These huge improvements might suggest that immortality is within our grasp. But it is important to understand the reasons for these improvements. If we do this, it becomes clear that it will be increasingly difficult to produce similar gains in the future. So, what have been the key reasons for advances in longevity?

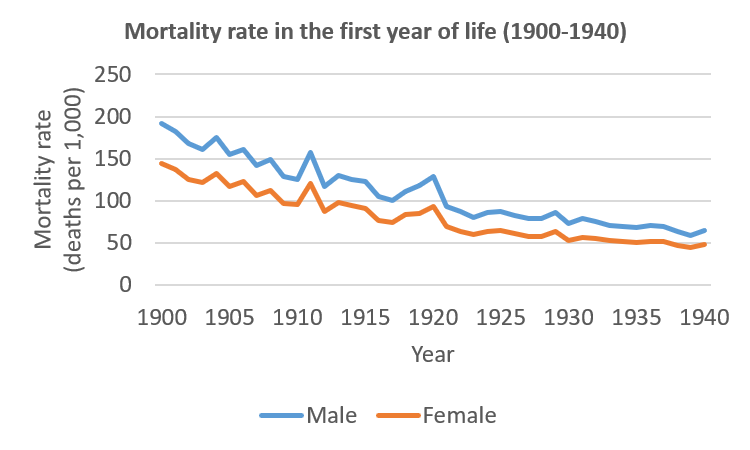

Infant mortality

Infant mortality might not seem that relevant to life expectancy, but it actually has the biggest impact of mortality at any age. In fact, if the probability of a child surviving its first year increases by 10%, the child’s life expectancy increases by 10%. Think of it this way. The impact of reduced mortality for a 90 year-old will only benefit those who have already made it to age 90. But reducing infant mortality improves subsequent life expectancy for all people born after this improvement.

At the start of the twentieth century, improvements in public health led to an astonishing fall in infant mortality, as shown here. In 1900, of every 1,000 boys born, 191 would die before their first birthday; by 1940, this number had fallen to 64. The improvements since then have been no less impressive – in 2013, only 4 boys in a 1,000 would die in their first year. However, the impact on life expectancy was most pronounced in those first 40 years.

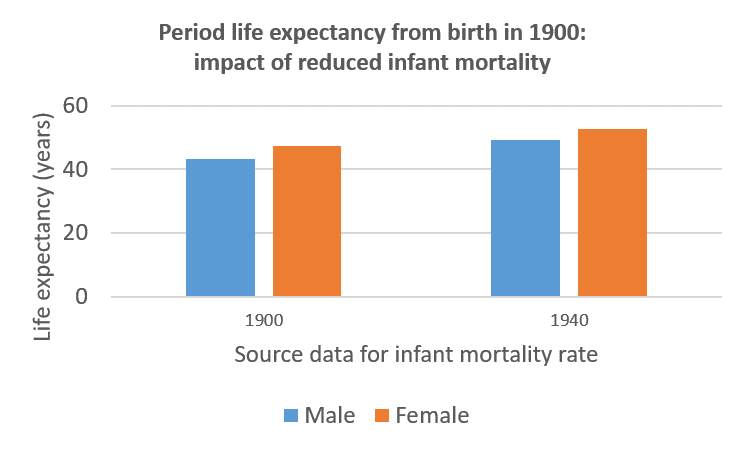

In fact, the impact of those falls in mortality in the first year of life alone would have been sufficient to raise male life expectancy from 43.3 to 49.2 years, and female life expectancy from 47.3 to 52.6 years, as shown here.

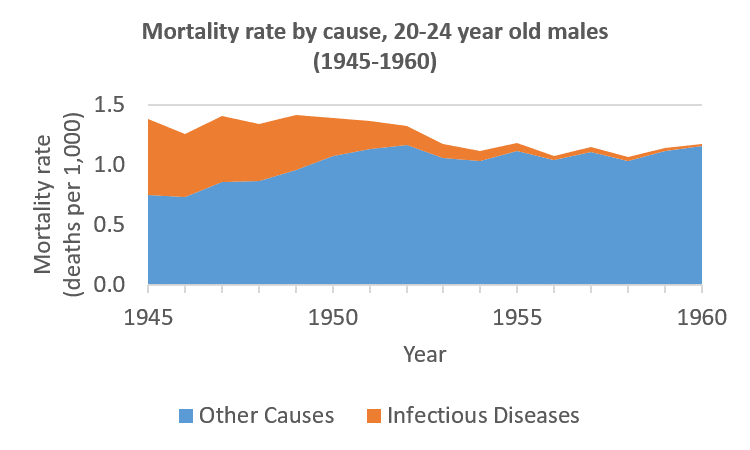

Infectious diseases

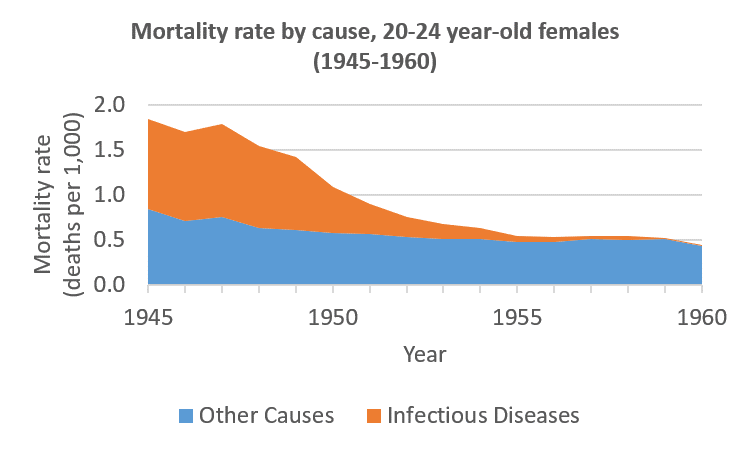

At the end of the Second World War, infectious diseases were still a major cause of death. In fact, for 20-24 year olds, infectious diseases accounted for 46% of male deaths and 54% of female deaths. However, the end of the war coincided with two key developments in the UK. The first was universal healthcare, in the form of the National Health Service; and the second was the availability of antibiotics. This reduced deaths from infectious diseases to near-negligible levels in just a quarter of a century, as shown here.

The result on overall mortality rates was profound, despite the fact fact that rising traffic deaths caused male mortality rates from other causes for those aged 20-24 to increase over the same period.

Smoking

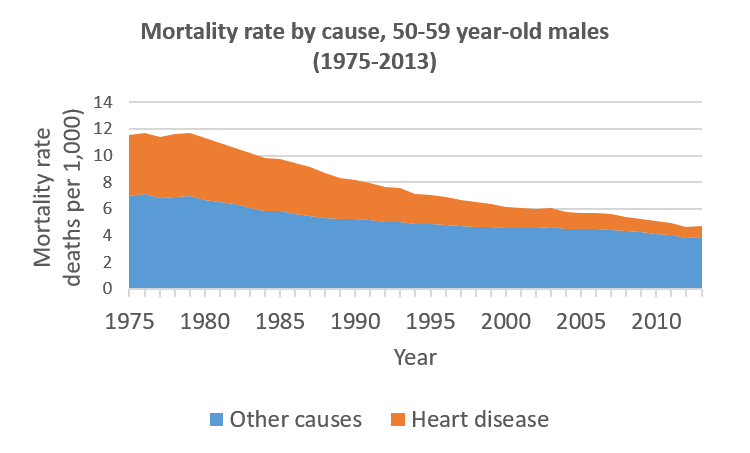

Another group of illnesses that has seen as steep decline is circulatory diseases. Take heart disease, for example. In 1975, this accounted for almost 40% of deaths for men aged 50-59. But by 2013, only 18% of men in this age group were dying from heart disease, as shown here.

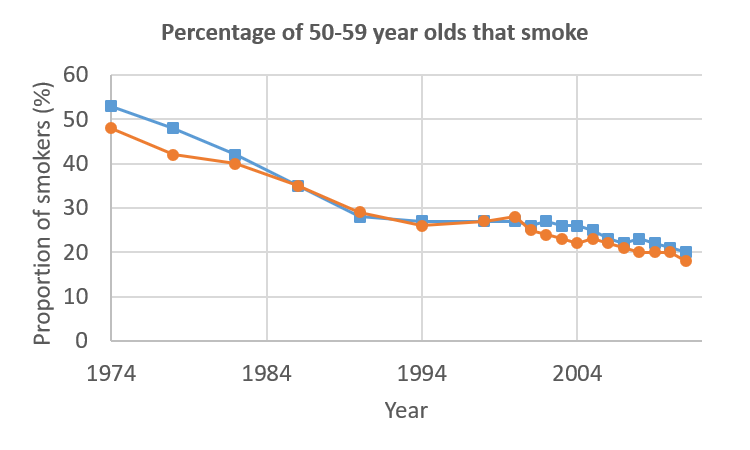

There are a number of causes for this improvement, but key amongst them is the fall in the number of smokers. As shown below, the proportion of male smokers aged 50-59 more than halved over this period.

These three causes for improvement have a two key features in common. The first is that they are difficult to replicate. Once infant mortality has been reduced to near-zero, it cannot be reduced to near-zero again; the number of deaths from infectious diseases cannot be reduced by much more (and, given increasing resistance to antibiotics, may actually rise); and people who have given up smoking can only benefit from that choice once. In other words, these improvements have already been banked, and cannot be banked again.

The second common factor is that all of these improvements were not just improvements in a single disease: they affected one or more groups of diseases. Improvements in infant mortality came about because improved care cut deaths from a number of causes. Antibiotics – and the NHS – improved survival from a whole range of infectious diseases. And stopping smoking doesn’t just reduce the risk of death from heart disease, it also has an impact on mortality from strokes, respiratory diseases and a whole range of cancers. It is hard to think of future developments that could have such a profound effect.

The outlook for cancer

So far, improvements have been largely confined to individual types of cancer. However, within these types, there have been significant breakthroughs. The genetic make-up of a cancer is used to determine exactly which drugs might give the best results. There are even tailored treatments that use the body’s immune system to fight tumours.

Even more exciting is the prospect of immunising against certain cancers. For example, 90% of cervical cancer cases are caused by viruses. As a result, existing cervical cancer vaccines could reduce cases of this disease by 70% in a generation.

But these victories are hard-won, and whilst progress is being made, the results are unlikely to be as spectacular as those seen when someone simply stops smoking, simply because these improvements are – by necessity – tackling one type of cancer at a time.

The obesity epidemic

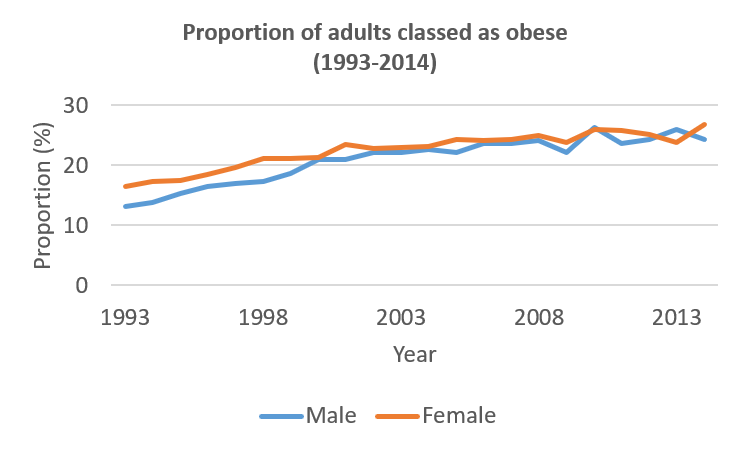

As medical science seeks to extend our lives, we seem to be intent on creating further challenges. Consider the obesity epidemic. Rates of obesity rose sharply through the 1990s, and have not improved in recent years. This is resulting in higher cases of type 2 diabetes, and may undo much of the progress made with heart disease and a range of cancers.

There are initiatives to try to reverse this trend. Some retail developments are designed with parking slightly further from the shops, and with stairs to encourage exercise; there are healthy eating campaigns; and there are proposals for unhealthy foods to be taxed. But with some believing that junk food is as addictive as tobacco or even heroin, this is another battle that will take time to win.

Limits to longevity

A key challenge with many medical advances is that they aim to treat the diseases caused by the ageing of the body – but that they do no seek to deal with ageing itself. And there are some who believe that trying to tackle ageing might be beyond us.

Ageing seems to be related to DNA at the end of each chromosome – telomeres – that protect the bulk of a cell’s DNA when it divides. Telomeres get shorter with each cell division. When the telomeres have gone, a cell can no longer divide and it dies. Could we increase the length of telomeres? Well there is an enzyme – telomerase – that can do just this. But having cells that do die is one way of stopping cancerous cells from proliferating, so having immortal cells is unlikely to bring immortality.

There is some evidence that severely limiting the amount you eat could make you live longer – but would you want to live longer if you were hungry all the time?

Looking across the animal world suggests further problems we might face if we seek immortality. Those species that live the longest are those that continue to grow, slowly, throughout their lives. Notwithstanding the obesity epidemic, we are clearly not a species where indefinite growth is an option.

More practically, it seems that for those species we resemble, longevity is linked to reproductive lifespan. This link even appears to hold within a species – women who have a later natural menopause tend to live longer. But using this information to increase longevity would take some serious medical advancements.

All of this suggests that whilst life expectancy has improved significantly in the past, future improvements may be more measured. The focus is now largely on treating diseases rather than removing risk factors, and the prospects for slowing ageing seem remote.

But significant resources are being focussed on dealing with the diseases of old age. Progress is being made not just with treatments for cancer, but with illnesses such as Alzheimer’s disease. This might mean that having already helped people to live longer, we might be able to enjoy a healthier old age in the future.

![]()